User-Informed Legal Design: A Practical Guide

Last Updated: 4/23/25

Introduction

What is UX design? When we talk about user experience—or “UX”—design, we’re talking about designing the entire experience of using a thing, not just designing the thing itself. You could make a functioning tool all by yourself, but if the people you made it for have trouble using it, or don’t want to use it, or can’t even find it in the first place, is it “useful” in any meaningful sense? Making something useful means making something that actually meets people’s needs—and that requires learning from users throughout the design process.

Why should legal services providers care about UX design? Lawyers and legal professionals undergo specialized training in order to understand the law and hone our advocacy skills. While this expert mindset can be useful, it can also make it difficult for us to recognize, seek out, and value less institutionalized forms of expertise, like the lived experiences of the communities we work with. If we want to design tools that actually help people understand and navigate legal problems, we will need to start treating our clients as collaborators. User-informed design processes can help us move beyond the traditional expert-client relationship and facilitate meaningful exchanges of knowledge that flow in both directions.

Moving from a design model with no user input to a user-informed design

So, how might the legal services community become more familiar with user-informed design principles and more capable and committed to applying them to the creation of legal resources? This report describes and furthers the Michigan Advocacy Program’s efforts funded by the Legal Services Corporation and executed in partnership with the Graphic Advocacy Project to explore this question. By using plain language and visual design, providing concrete examples, and anchoring UX design concepts in the access-to-justice context, we hope to create an accessible resource that will both persuade the broader legal services community of the importance of undertaking user-informed design and arm them with the tools to do so.

UX Design Process Overview

User experience (UX) design, also known as human-centered design or user-informed design, is a problem-solving approach that brings the people you’re designing for into the design process. Born from design thinking, it pulls principles and methodologies from spaces including sociology, psychology, and ergonomics, to name a few. The core principles of UX design make it applicable to many different spaces and issue areas, including how people interact with legal systems, processes, and information. Though the design process may vary from project to project, there are a few core principles that govern user-informed design:

- Focus on the people that are directly affected by the issues you are working on, and consider all of the people associated with those issues.

- Find the right problem: seek the fundamental root problems and not just the symptoms.

- Everything is part of a system: understand how things are interconnected.

So how do you actually go about “doing” user-informed legal design?

User-informed design is a set of methods and mindsets that facilitates user input throughout an iterative problem-solving process. Though user-informed design is often associated with technology solutions, it is not limited to tech. Solutions come in all shapes and sizes, depending on user insights—from updating a short pamphlet about tenants’ legal rights, to creating a comprehensive statewide legal help website from scratch, to reimagining your organization’s intake processes. Whether you’re tackling something broad or honing in on something specific, creating something new or improving something old, you can leverage this process to ground solutions in your users’ experiences and needs. And while the process will look a bit different for every project, the elements are the same.

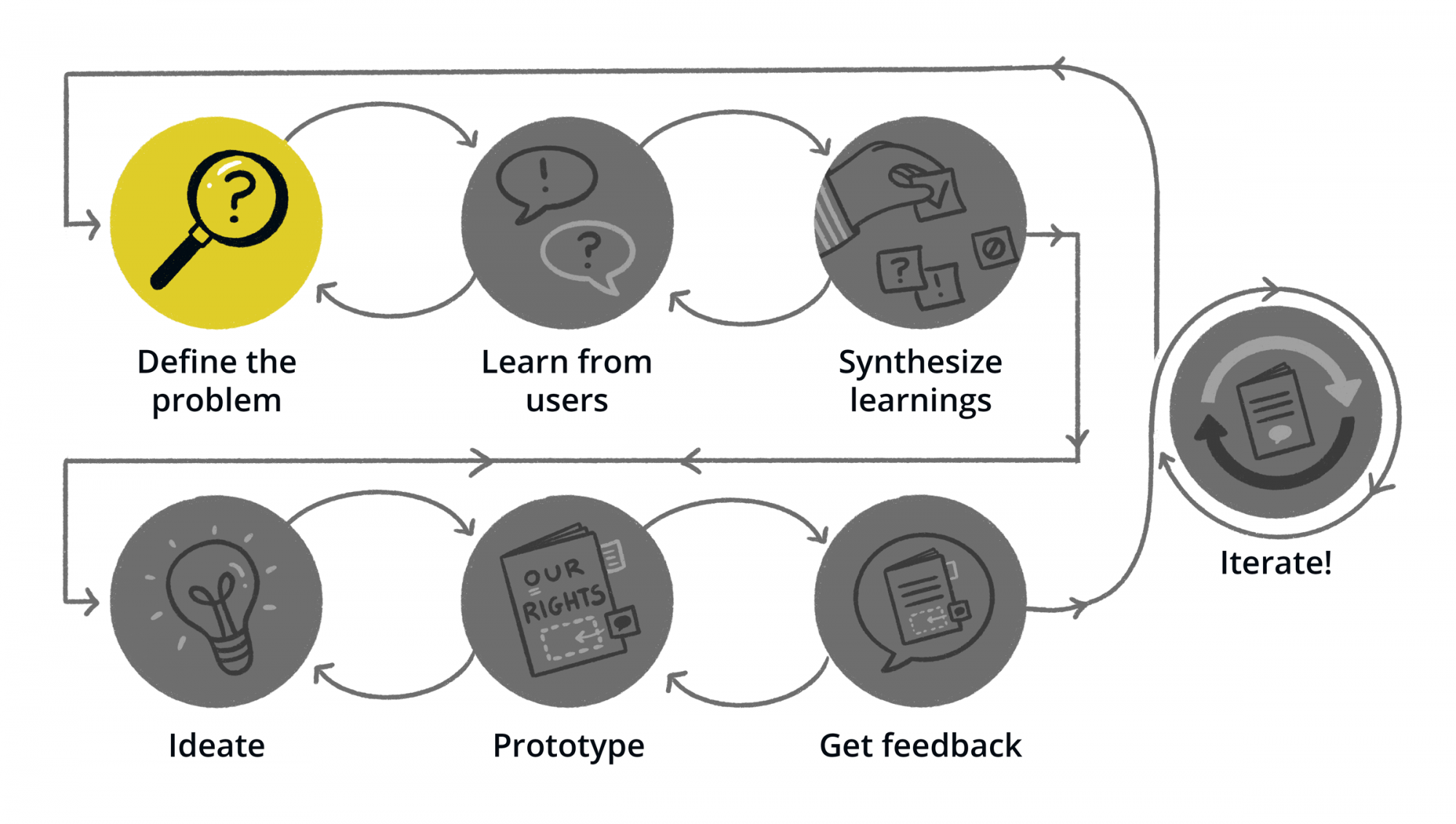

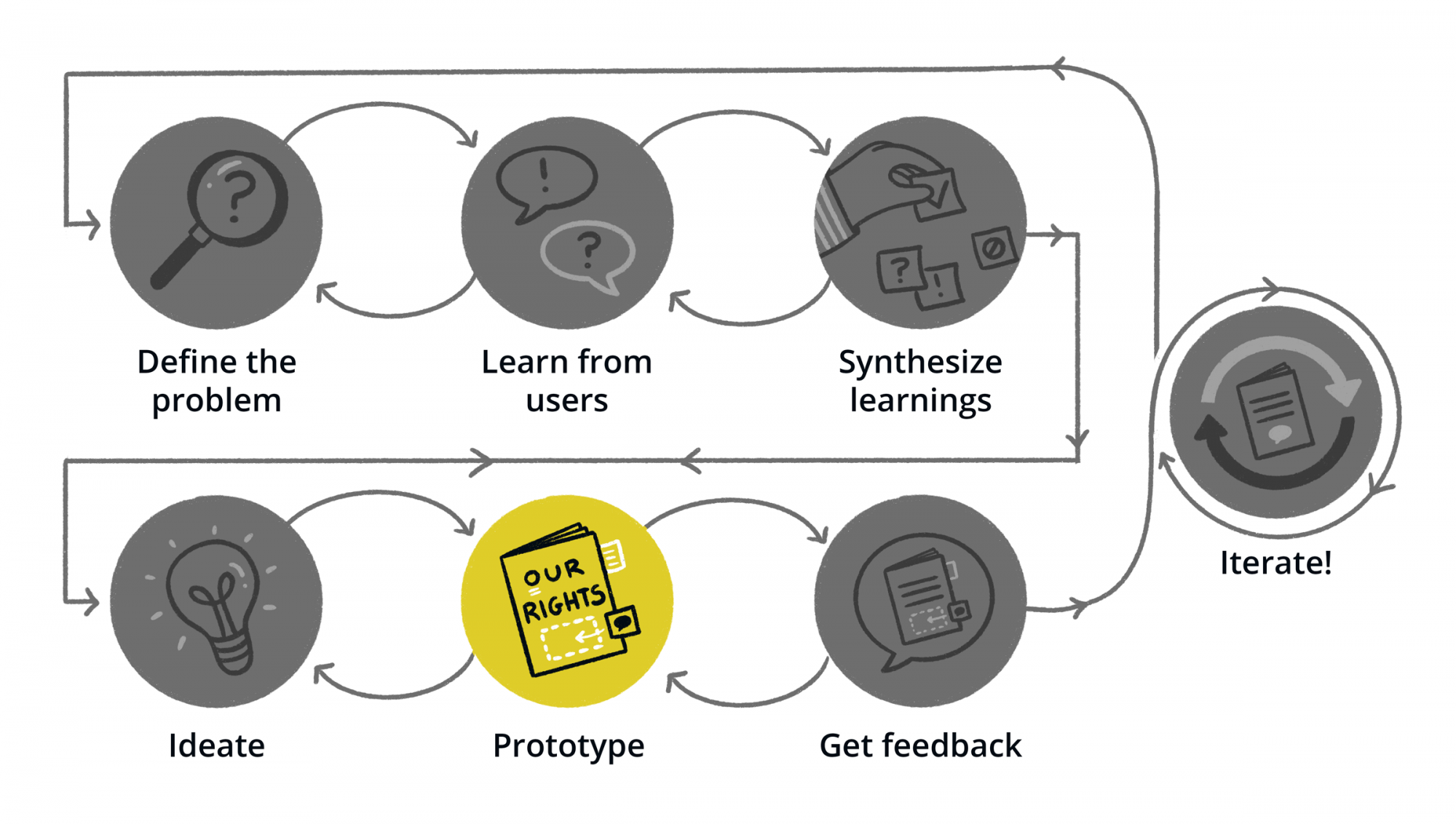

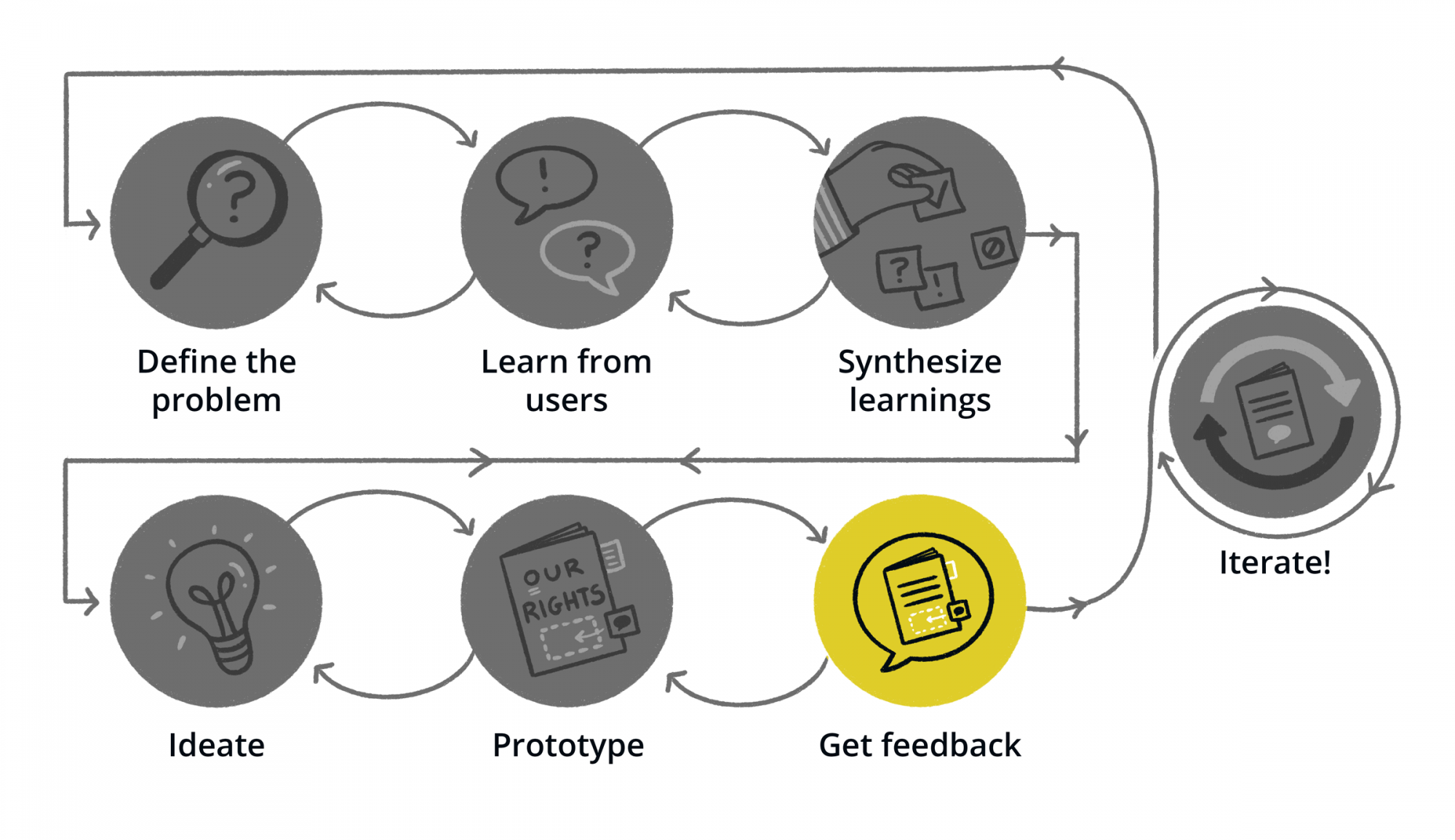

An overview of the user-informed design process

At the heart of user-informed legal design is the intention to bring those who are most affected by a legal problem into the process of creating a solution to address it. This process begins with learning from individuals and communities about the challenges they face and their lived experiences. Such insights drive a deep understanding of the problem at hand, challenging our own singular assumptions and providing a basis to ideate solutions that directly address people’s needs. As we move through the design process, we must continuously and intentionally create opportunities to connect with impacted individuals and communities in order to keep solutions rooted in their experiences of the problem. This process keeps the people who become users of the intended solution at the center of the problem-solving process to ensure solutions are accessible and meet their needs.

Let’s take a closer look at each stage of the user-informed design process.

Define the problem

Approach problems by first determining and defining the problem space as you understand it.

Start by defining the problem space

To start this process, we begin by first defining the problem space. This can be done by documenting what you already know about the problem, who it affects, existing solutions and assumptions, and what you still need to learn as a starting point for further discovery. While it's natural to jump to solutions and problem-solving, it is important to first start with understanding the problem so that solutions are not simply reactive, but will truly address the issues at hand. This upfront planning stage, often documented in an early-stage project brief, helps to gauge what information still needs to be gathered and learned from those most affected by the problem, your users, as well as considerations for future solutioning.

Resources

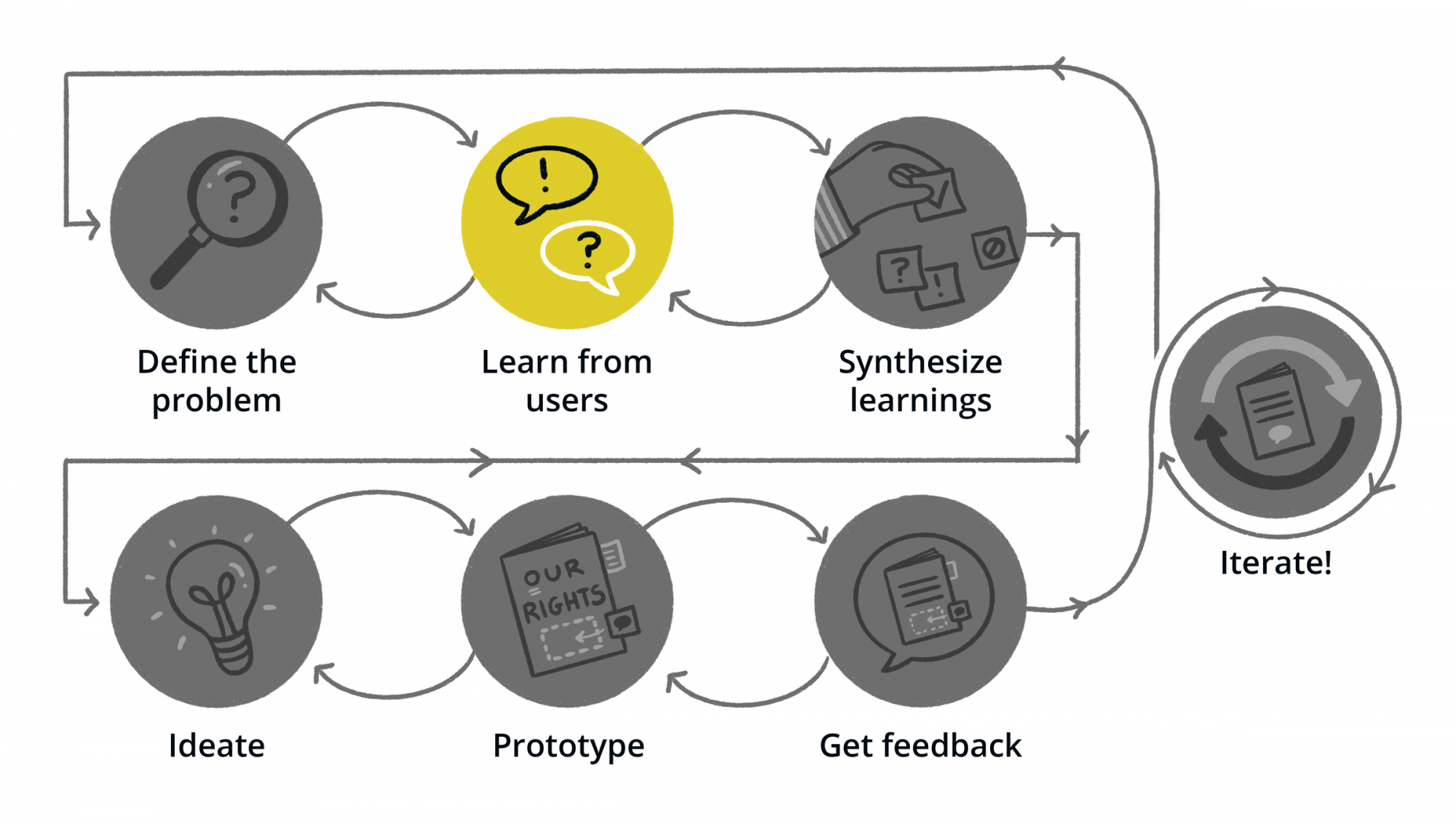

Learn from users

Explore the problem space by learning from those who are affected by the problem (and those who might affect it).

Determine what else you need to learn from users

After defining the problem space and determining which research questions to explore, engage with those impacted by the problem to further discover and contextualize the problem space. You can use a variety of research methods and activities to learn more about users' processes, needs, and pain points, making space for users to participate in the design process. Start this process by first creating a research plan to catalog what it is you’re hoping to learn and from whom, and to prepare for connecting with participants to gather information.

Remember to include all potential users in this stage—for example, agency staff assessing people’s eligibility for a public benefit as well as individuals applying for those public benefits. This ensures that solutions will truly address all users' needs and not be biased by our own assumptions and perspectives.

This early research opportunity to connect with those in the problem space is best achieved by utilizing exploratory research methods that allow for open-ended and ethnographic discovery and learning from users. A common method employed at this stage is semi-structured interviews that allow for participants to share their stories and for you to probe into areas of interest.

Overview of research methods (snippet from UX Design & Usability Testing course)

How to prepare for and conduct interviews (snippet from UX Design & Usability Testing course)

Resources

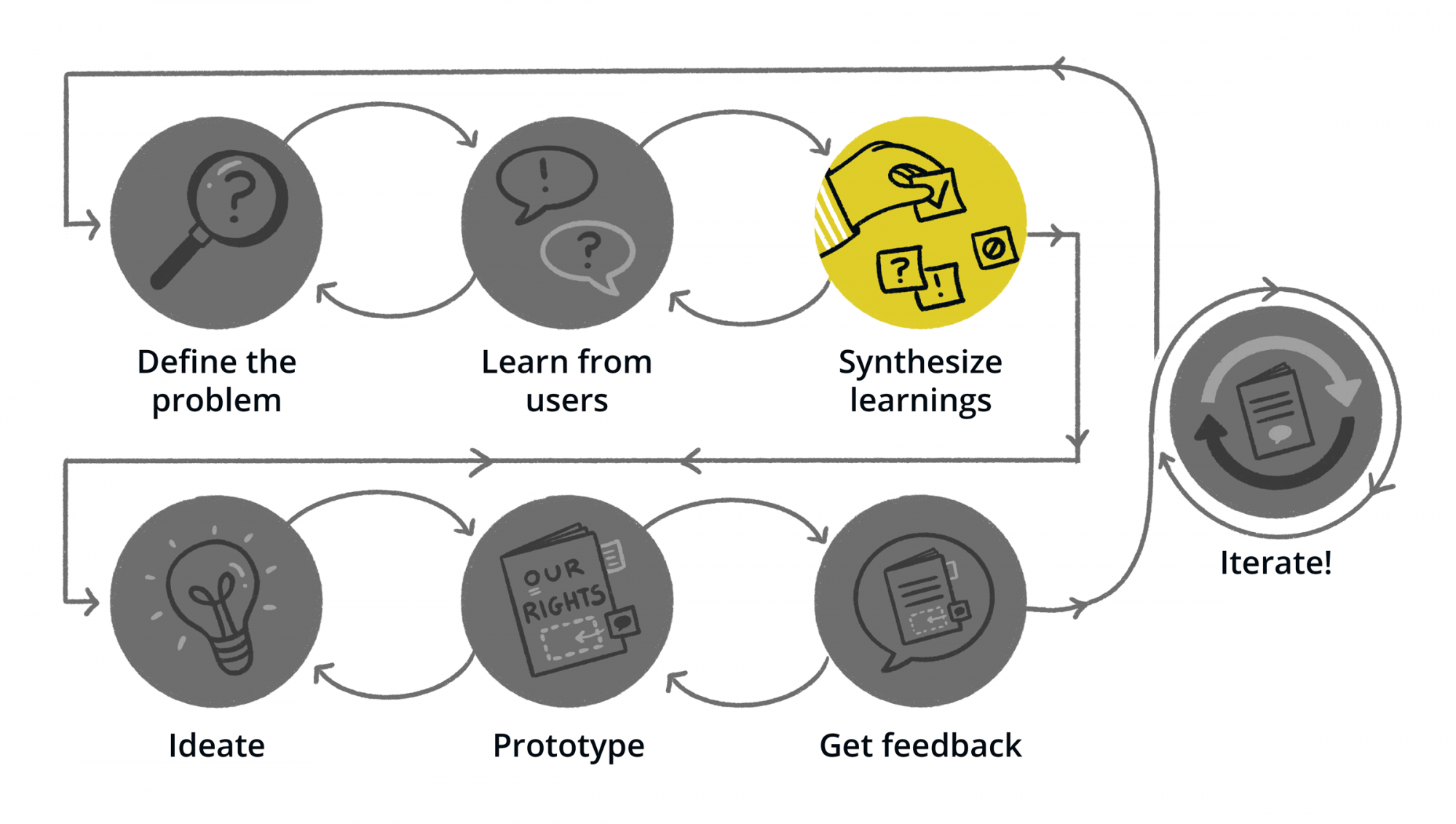

Synthesize learnings into insights

Review learnings from research to discover patterns and themes that can be synthesized into high-level insights for informing solutions and next steps.

Synthesize learnings from users into insights

After conducting research and learning from users, it is important to take time to make sense of that information before jumping to solutioning. Synthesizing learnings from users into high-level insights can help better define the problem space (and what to do about it). This stage of the process can reveal the most frequently encountered, critical, and even surprising pain points and needs as well as provide a more thorough and holistic picture of the end-to-end user experience. Insights can then be used to create artifacts to help visualize and ground the problem in users’ needs, values, and expectations and identify opportunity areas for potential solutions.

One way to make sense of data collected through user research is by grouping takeaways into patterns and themes, which will then become high-level insights. While there are many ways to do this, insights mapping is a common approach that uses sticky notes to facilitate easy grouping and naming of insights. You can create an insights map by yourself or collaboratively with your team, and you can use physical sticky notes or virtual ones in tools like MURAL. Start by writing takeaways from each interview, survey, or other research effort onto sticky notes—one takeaway per note. Next, move the sticky notes around to cluster related takeaways together. Finally, review each cluster of insights to determine its overarching theme. This exercise can help you identify patterns in your research, translating a range of user input and experiences into applicable insights.

How to synthesize learnings from users using affinity mapping

(snippet from UX Design & Usability Testing course)

Resources

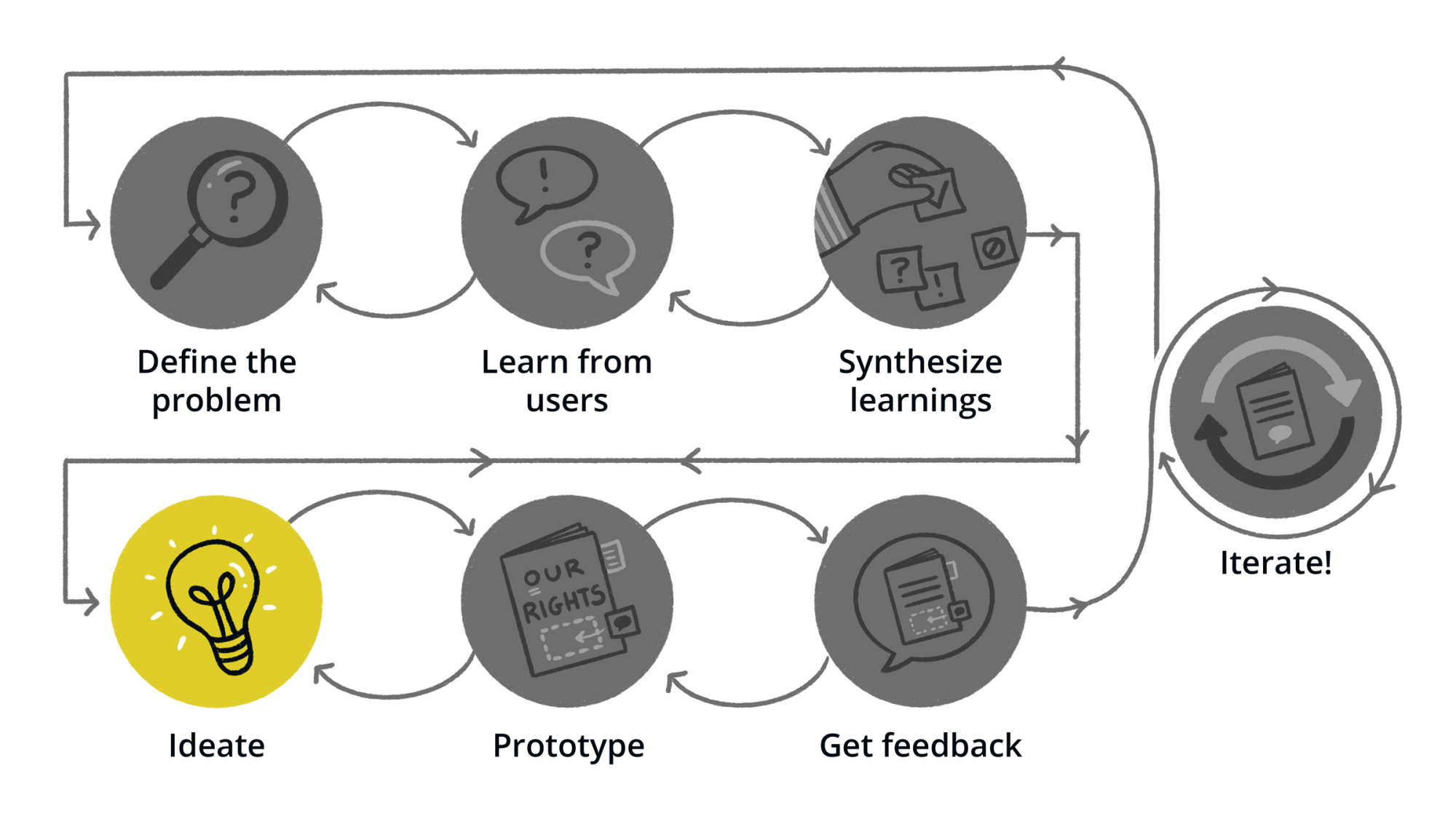

Ideate

Look for insights that speak to current pain points, missed opportunities, and/or disconnected processes. Brainstorm all possible ideas that address users’ needs, then hone in on those that are both achievable and impactful.

Use user insights to ideate on potential solutions

Ideation is the process of turning research insights into potential solutions through brainstorming. Ideation can be daunting (but fun), which is why it’s important to lean on what you’ve learned from your users to drive ideas and next steps. Review your research synthesis for insights that highlight current challenges or pain points, missed opportunities, and/or disconnected processes. Brainstorm all of the possible solutions that might address those insights. Start broadly to create space for creativity, then hone in on specific ideas. Focus on ideas that will have the highest impact, meet the real world context, and consider all given constraints: these ideas will not only keep users at the center of the solution, but also have the best chance of success.

One way to evaluate potential solutions is by mapping them on a prioritization matrix, with one axis representing the potential impact of the solution and the other axis representing the feasibility of executing the solution. Assessing each solution on these two axes, as well as relative to each other, can help clarify where best to invest resources while also creating the best user experience.

Overview of prioritization using an impact feasibility matrix

(snippet from UX Design & Usability Testing course)

Resources

Prototype

Prototypes help you think through a solution more thoroughly and facilitate gathering feedback from users to inform early iterations and improvements.

Chose an idea to prototype and explore

A prototype is a preliminary model or simulation of a solution. Prototypes are a great way to bring ideas to life without expending a lot of resources. They are a lightweight way to help visualize and assess potential solutions and can be created in different levels of fidelity—from a hand-drawn paper prototype to a live demo of a website—depending on your capacity and goals. Prototypes simulate solutions in a way that does not require them to be completely developed, helping us think through user experience questions—like how the information flows from one page to the next, whether actions are accessible and visible to users, and whether the purpose of the solution addresses the identified challenges and opportunities from research synthesis. Most importantly, we can use prototypes to gather and implement feedback from our users.

There is no “right” way to create a prototype: it depends on your capabilities, resources, and needs. There are existing tools and approaches that can help you bring your ideas to life through prototyping, without needing to invest time and resources into learning additional skills.

Resources

Get feedback/Usability testing

Gather feedback from users on working prototypes to assess how well solutions meet users' needs and to inform future iterations and improvements.

Validate and test usability of initial prototypes by getting more feedback from users

Gathering feedback on initial prototypes and ideas is an important way to keep your users involved in the design process. By soliciting feedback early and often, you can quickly determine whether your solutions truly address the problem and identify areas for improvement. Feedback keeps your focus on the users and their needs to ensure solutions are effective, usable, and successful.

Usability testing is a research method to help get feedback on prototypes in order to test early assumptions and inform future iterations (and potential pivots). During usability testing, research participants interact with your prototype while you observe their experience and solicit their initial impressions. When facilitating this process, your role is not to explain your design decisions or “correct” the participant’s use of your prototype, but to create space for the participant to explore the prototype as organically as possible and to give honest feedback.

Resources

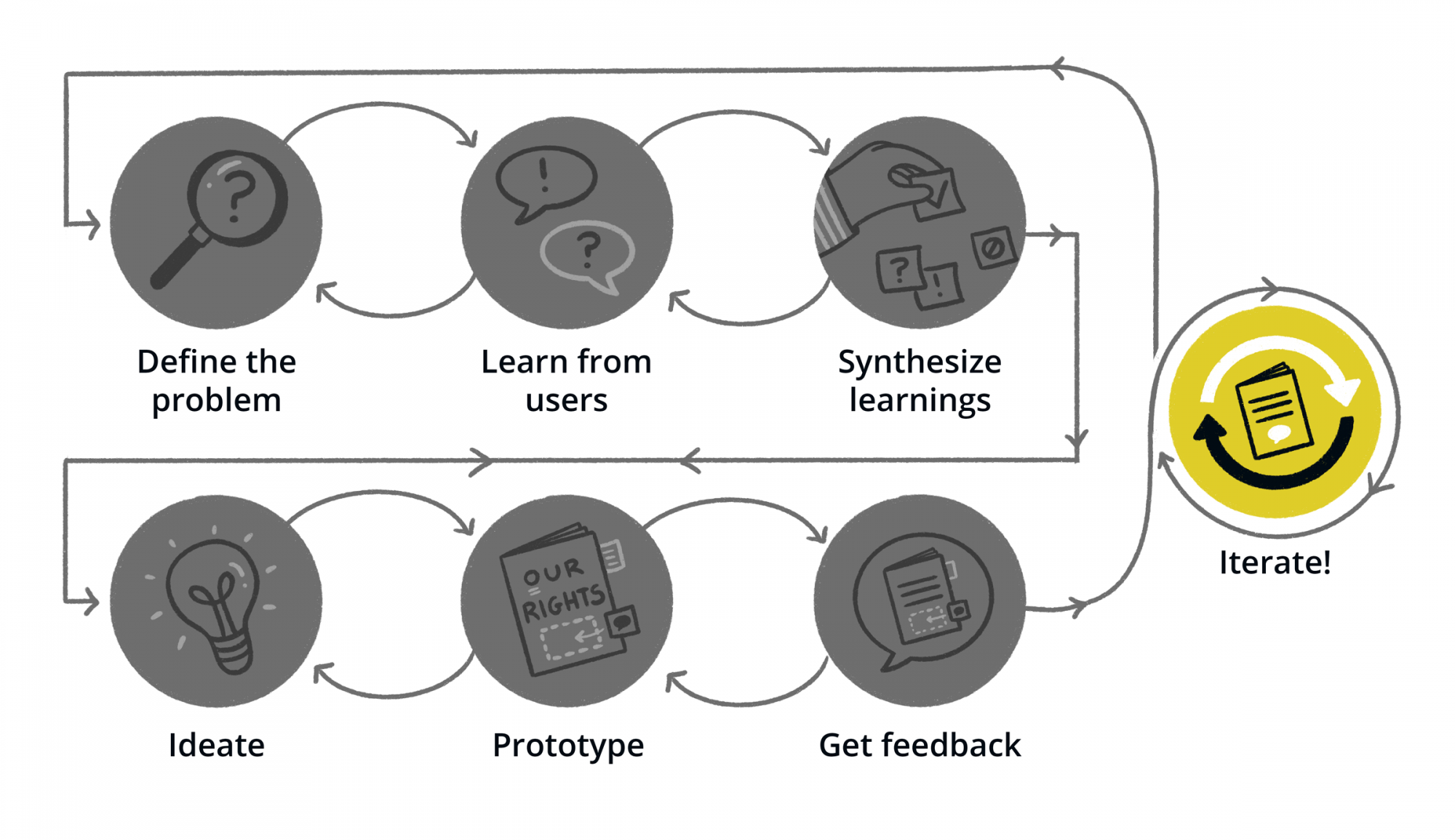

Iterate

Each phase of the UX design process builds upon what came before it, but the process is not linear. The design process is ongoing as we continue to gather feedback and learn from users as to where there are opportunities to improve.

Continue to build and improve on solutions by iterating

Iteration reminds us that design is never “finished”—that we always have the opportunity to refine our solutions to ensure they meet user needs. Whether you are updating content, tweaking interactions, or incorporating new media or imagery, your iterations should be based on user feedback. Iteration is an opportunity to continuously assess and ensure that your solutions center the people who are most affected by the problems motivating your design.

User Interface (UI) design resources:

- Usability heuristics

- Typography 101

- Checklist for a useful icon

- Color meanings & psychology

- Interaction patterns

- UX Archive

Explore other UX Design process models to see how they’ve made this process their own:

- Service Design Vancouver - Double Diamond

- IDEO.org - Design Kit

- Nielsen Norman Group - Design Thinking

Best Practices and Mindsets

Based on GAP’s experiences facilitating UX design training sessions with the justice community, as well as our broader participation in the field of legal design, we’ve identified a few best practices and mindsets for approaching user-informed design in the legal space.

- Leave your assumptions at the door.

- Be mindful not to insert your biases at any stage of this process, including research, synthesis, and ideating. Recognize users as experts in their situations.

- As legal professionals, we know how important it is to build trust with our clients. But traditional legal training teaches us to view these relationships as one-sided in terms of expertise: we know the law, and we just need to extract enough information from our clients to fit their situation into our preexisting legal analysis framework. User-informed design requires us to move away from this “lawyer as expert” mindset and recognize that our clients are experts in their own lived experiences. Our clients become our collaborators, sharing their knowledge with us just as we share ours with them.

- This best practice is crucial throughout the design process, but its value is particularly apparent at the research synthesis stage. Once we have gathered information about the problem from a variety of users and stakeholders, we face the challenge of distilling that information from disparate sources into cohesive takeaways that will inform our ideas for solutions. We’ve done the important work of seeking user input, but we will undo that work if, during synthesis, we try to cram our users’ knowledge and experiences into our own preconceived perspectives of the problem. Instead of trying to fit our users’ insights into our own pre-existing analytical frameworks, we must let the insights themselves reveal themes and patterns. Insights mapping, described above in the “Synthesize learnings” section of the process overview, is a useful method for approaching research synthesis with openness.

- Explore the problem before you jump to a solution.

- It is tempting to start thinking up solutions as soon as we identify a problem, but we can’t solve a problem that we don’t fully understand. Our own perspectives and assumptions can serve as hypotheses, but we must learn about the problem from people experiencing it before we can start to define the universe of potential solutions that will actually meet their needs.

- Many of our course participants experienced the value of this practice firsthand. They began their projects with assumptions about what their solutions would be, but speaking with users revealed dimensions of the problem they hadn’t considered. For example, one organization started with the expectation that their tenant advocacy tool would be tech-based, but after conducting exploratory research they learned that a one-page printed flyer might better serve their users’ needs.

- This best practice highlights the importance of understanding the different phases in the design process, particularly the different intentions between upfront exploratory user research and gathering feedback through usability testing. Exploratory research often focuses on building out the context of the problem space, learning about users’ current lived experiences related to a given issue or activity. Usability testing is a way to gather feedback about an existing solution (including prototypes), to identify areas of friction or confusion for users. It’s important to bring both methods into the design process to ensure that the solution both addresses a need and is usable.

- Approach the problem holistically.

- Only by understanding the problem space holistically can we begin to define a range of solutions. In order to do this, we need to bring different perspectives into the design process to gain an understanding of the root causes and entire ecosystem.

- In the legal space, there is a tendency to fit a problem into a predefined solution. Lawyers are trained to issue-spot, to fit a client’s experience into a pre-existing legal framework of what a “problem” looks like, to then utilize existing approaches to solve the problem. This approach might be useful for traditional legal representation, but it can hamper our efforts to design solutions that address how users actually experience a problem beyond the narrow legal conception of that problem.

- Gathering research from a broad range of perspectives helps us gain a more comprehensive understanding of the problem, including its divergent impacts on (and by) different people, its interactions with other related problems, and its root causes. Approaching the problem holistically also helps us expand our universe of possible solutions, including solutions that arise before, after, or entirely outside of legal processes.

- It’s also important to consider where a solution may fall into an existing ecosystem. Understanding where and how people currently seek and interact with existing solutions is critical to making sure a new solution is discoverable and accessible. When we zoom out and think holistically about the ecosystems in which we are designing, we make space for opportunities like outreach partnerships and new ways of distributing information as potential solutions.

- ITERATE! This process never stops.

- You can leverage the user-informed design process at different and multiple phases of your project, depending on your needs and resources. Do you have an existing resource that you want to improve? Do you want to learn more about your potential users and how they are navigating and connecting with legal resources more broadly? Starting with a research plan or a project brief can help to clarify where to begin in the process.

- The best part about the user-informed design process is that we never stop learning. Every opportunity we have to connect with people is an opportunity to learn more about their experiences and develop awareness and empathy. An iterative mindset helps you remain an active participant, invested in understanding how to continuously improve resources and continuously evolve your understanding of those you intend to serve.

- Additional best practices

- Don’t start from scratch—leverage existing research and knowledge! For example, your organization may already offer a hotline or support center that is regularly gathering questions or concerns from your community. There is so much to learn from these existing touchpoints and interactions.

- Design with real content. When creating designs, try to avoid designing with lorem ipsum or placeholder text. Especially in the legal space where information is critical, let the content inform the design. Think about the content that your user is coming to your tool to find. Answering these questions first can help to avoid visual design decisions that don’t support the content.

- UX is not just what the tool looks like. As we’ve reiterated throughout the process, the user experience is not limited to what the “thing” looks like, but all the different ways that a user engages with the “thing” including how they discover, access, and use it.

- Consider accessibility early on. When you are designing a new solution, begin with accessibility in mind to inform your design decisions. An impactful and successful solution is one that works for all users, including those that may use assistive technology or simply require information to be conveyed in a different way. Part IV of this report includes resources for ensuring accessibility.

- Prototype before you build anything! Prototypes bring solutions to life early and with low effort, and aid in thinking through a proposed solution. Even low fidelity prototypes like paper prototypes can reveal gaps or opportunities for improvements and create space for iteration.

- Solutions come in all shapes and sizes (forms, outreach strategy, collaborating with hotline centers to gather FAQs, guides, interviews). As mentioned above, UX is not just the design of the “thing”. To follow that same line of thinking, a solution might not be a “thing” at all. It could be a process or a practice rather than a physical object to help users accomplish their intended task.

- Keep things simple and consistent. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel or over-design resources. Use interaction patterns that are common and familiar to users. Present information in a clear and clean way. Part IV includes design resources to help you achieve simplicity.

Challenges

During this project, GAP observed that justice community members repeatedly encountered certain challenges when applying user-informed design methods to their work. Here are some commonly-asked questions and our best attempts to answer them!

How do I recruit participants for user research and usability testing? When it comes to recruiting participants, remember that you’re not starting from scratch: you probably interact with your users and other organizations that serve them on a daily basis! Start by defining user groups and participant criteria so you can aim for a representative sample of participants. Think about how different user groups might require different recruitment techniques. For example, a feedback field on your site might reach a user who’s having a frustrating experience with your site, but it won’t reach a potential user who doesn’t even know about your site. Leverage existing relationships and partnerships to conduct new outreach online and on the ground. Whenever possible, reimburse people for the costs of participating and offer incentives in return for their time. Outreach can take time and cost money, but when possible, invest! The feedback you’ll receive, the lessons you’ll learn, and the relationships you’ll build will be well worth it.

How do I conduct user research and usability testing when in-person interactions are impossible or highly limited? As COVID-19 has shown us, remote user research and usability testing may not be ideal, but it can be done! When recruiting participants, try using existing opportunities to connect, like remote workshops or social media engagements—people will be glad to be heard. There are many remote tools available for gathering research and feedback, but most of the time all you need is a phone.

How do I conduct research and collect feedback as a neutral entity, like a court? If you represent the legal system, it may be especially difficult to build trust with participants and facilitate conditions under which they feel comfortable speaking with you. Be open and honest: acknowledge your institution’s limitations. Emphasize that participating in user research is an opportunity to be heard—and potentially change things. If you keep at it, you’ll become known as an organization that is open and responsive to feedback, and people will start telling you things you didn’t even ask for!

How can I iterate on existing tools with limited resources? If you have the capacity to build a brand new tool through a robust user-informed design process, that’s awesome! But for many members of the justice community, time and resources are in short supply, organizational buy-in is difficult to muster, and existing tools stick around despite their flaws because they’re better than nothing. Luckily, existing tools don’t just create constraints—they also present opportunities to iterate. Small changes can make a huge difference. Keep non-tech improvements in mind: changing up your outreach strategies or your content can transform a user’s experience of a tool.

How can my organization embed user-informed design processes into our ongoing work? Adoption, mindset shifts, and buy-in are critical for creating space for user-informed design. You’re probably already doing a lot of work that will lend itself naturally to user-informed design projects if you approach it with that intention. For example, you can leverage routine interactions with clients to gain exploratory insights into problems and solicit feedback. Try adding feedback surveys to your websites or asking for feedback in-person after a process is complete. It can be challenging to recruit users while they’re in the middle of navigating complex legal processes; invite users to give feedback in the future and build a participant database. And continue to build partnerships with community organizations and nonprofits that work with the same communities as you; you can help each other reach users and disseminate information.

View the full report here: Build a better _____: Strategies for User-Informed Legal Design

Please give us feedback!

Since you just read this material, you know how crucial user feedback is for designing a useful resource. Was this report helpful? Did you find the information you were looking for?

Please let us know by taking our quick survey. We promise it is very short and very important! The LSC Technology Initiative Grant program’s continued funding depends on our ability to measure the impact of projects like this one. Your feedback could help fund future access-to-justice technology projects! Thank you so much for your time.

ADD DETAILS about Michigan Advocacy Program.

The Graphic Advocacy Project is a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to shifting legal knowledge and power to marginalized communities. In collaboration with these communities and the legal advocates who work alongside them, GAP uses participatory design processes and visual communication tools to create legal resources that engage, inform, and mobilize. Our clients are legal service providers, advocacy nonprofits, community lawyering organizations, academic institutions: anyone using law to effect social justice. We view our clients as partners in carrying out our shared mission, and strive to maintain open channels of communication and feedback throughout the life of each project. GAP has assembled a team of three for this project: Ashley Treni, Victoria Suwardiman, and Hallie Jay Pope. Our respective areas of expertise are symbiotic but distinct, allowing us to draw from multiple perspectives and methodologies.

| Victoria specializes in user research and UX strategy, with past experience working on tools for nonprofits, associations, higher education institutions, and government clients. As an avid mentor, she is well equipped to support newcomers to the technology design world. |

| Ashley is a UX designer, researcher, and educator. Having served as co-founder and design director for JustFix.nyc, she is intimately acquainted with the unique challenges of designing a legal tech tool. |

| Hallie is a lawyer and visual communicator. Her work focuses on using design and narrative to distill complex concepts and share knowledge. |